Will Pension Strikes Reform UK Higher Education?

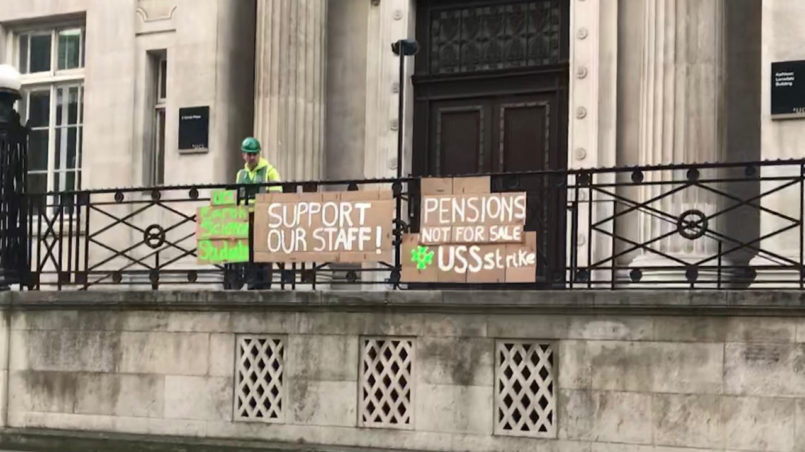

Strikes for the “axed” pensions of academic staff have taken UK universities by storm. As members of the University and College Union (UCU), the academic faculty of 62 universities (a number which is yet to increase) has started the biggest union strike action so far. The Union has been on strike for 14 days spread over the last four weeks of term 2 and plans to continue into exam period.

The strikes are due to a proposed reform to the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), which could leave lecturers with almost £10,000 less a year in their retirement plan.

In the new proposed pension plan, USS will change the currently defined benefit scheme, which gives members a secure retirement plan to a defined contribution scheme, in which pensions are subject to changes in the stock market.

The proposed plan has provoked strike actions in a high percentage of the academic staff in leading UK universities, including Oxford, Cambridge, University College London and many others. Universities UK (UKK) claims that the cuts are essential due to a £6bn deficit, and if the reform is not implemented, this will result in future cuts for academic staff and research funding.

The academic staff of 68 of 130 universities will be affected by the changes to the USS. In January, a majority of 64 universities, which are UCU members, voted in support of strike action.

Of course, there is a third party affected by the disputes between academics and the Universities UK organisation – the students. The strike was initially planned for 14 days, during which lecturers cancelled their lectures, office hours, research and also postponed grading assignments. However, due to the failure to reach an agreement between the lecturers and the USS, it is uncertain how long the strike is going to continue – it may even continue during the examination period in May, which will subsequently affect the exam grading period.

There is overall student support for the striking lecturers, and dissatisfaction with the management. However, with the end of the academic year approaching, the strikes definitely contribute to a feeling of anxiety and worry, and deprive students of valuable contact hours. Nevertheless, there was little information available to students prior to the strikes, and the feeling of uncertainty continues.

During strike action, lecturers and student strike supporters are distributing leaflets, calling on students to “Not cross the picket line“, the protest’s slogan, and to stay away from the campus. Sometimes protestors even become aggressive towards students who enter the campus and decide to go to lectures. Despite support for their striking lecturers, students cannot always afford to miss lectures and seminars, which is especially true for international students whose visa is dependent on their 70% attendance rate. Supporters suggest that student commitment and protest are the weakest point of attack vis-à-vis the universities’ management, which would pressure them into reversing the proposed pension cuts. Student participation has indeed increased as everyone continues to be affected.

An agreement offering an independent re-evaluation of the pension deficit and temporary arrangements to overcome the funding gap was almost reached on Tuesday, March 13th. However, through social media, especially Twitter, strikers expressed dissatisfaction with the proposed deal and urged the union leadership to leave the deal and push for a “more decisive victory”.

UK education is among the most expensive – costing domestic and EU students £9,250 a year (not considering the interest on student loans). This makes daily lectures very costly and inevitably raises the question of whether students will be compensated for the days of the strike, especially when lecturers are not paid for the days they are striking.

It seems that the initial panic of the final exams being affected has moved towards a focus on the financial aspect of the strikes, not only as regards the pension cuts, but also whether the cost of education is justified. The idea of higher education as a mere business equation has manifested itself clearly in the response with which the strike has been met. Universities have become one of the most profitable governmental areas. In the modern job market, higher education is no longer a luxury but a necessity, one with which many students have to comply with despite any decisions by the governmental management such as the tuition increase since 2012.

The strikes are no longer only about the pension cuts; this is just one manifestation of a problem that many universities’ leaders believe is rooted in the politicalisation of higher education in the UK. In an open letter, the President of the Cambridge University Students’ Union has argued that the strikes and demonstrations are “about the future of higher education, continued marketisation and the move towards students as consumers“. The ever-growing demand for university attendants does not proportionally answer the needed positions in the market. However, student places and marketing of university education are continuously increasing, leaving a discrepancy between employment possibilities and expectations.

The position of students as consumers shifts their inherent position from innovators and discoverers to passive recipients of ideas from lecturers.

In an open letter answer, the Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University argues that “resentment has been building steadily, rooted in a widely shared sentiment that policies pursued by successive governments over two decades are fundamentally damaging British higher education“.1

Furthermore, the central public talk about UK universities has not focused on their position as creative and innovative hubs, but broken pieces in need of “market discipline“. The Vice-Chancellor, Prof Stephen Toope concludes: “The focus should be on what values our society expects to see reflected in our universities, not just value for money.”

The strikes have ignited not only long-rooted dissatisfaction and concerns with the UK higher education system but have also sparked a much-needed discourse for the future of this educational system. Will the pension strikes lead to a reform of higher education in the UK?

_

1 https://www.cam.ac.uk/news/the-future-of-uk-universities-vice-chancellors-blog