The Doctor on the Migration Frontline

Pietro Bartolo has the look of someone who has seen too much suffering and death. But still has hope.

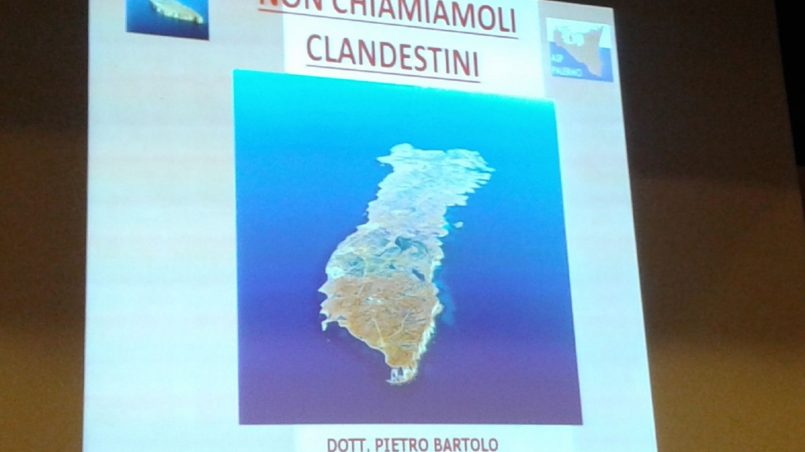

He is the director of the small hospital on the Italian island of Lampedusa, a small slab in the Mediterranean Sea, closer to Tunisia and Libya than to Sicily or mainland Italy. In more than 20 years on the frontline of the migrant crisis, Dr Bartolo has met and examined more than 250,000 men, women and children. Some of them in body bags.

Many of us remember him with little Favour in his arms, in a picture that went viral around the world. Favour, whose name means “privileged”. She arrived in May at the island’s tiny port completely alone, only nine months old, with a little blue woollen hat. Her mother, pregnant with another child, died of petrol burns in the dinghy that should have brought them to safety.

“I asked for custody of her, but they said I’m too old”, says Dr Bartolo.

For others he is the doctor in the award winning documentary Fire At Sea (Fuocoammare), which captures life on the Italian island. A documentary about the European migrant crisis which was broadcast throughout Italy on 3rd October, the first national day of remembrance for the victims of migration.

Since 27th September he is also known as the doctor on the cover of Tears of Salt (Lacrime di sale), in which Dr Bartolo writes about his childhood in Lampedusa and the struggles he faces at the dock and at the island’s small hospital. For me he is a great and extremely humane man whom I had the chance to listen to and with whom I had a very brief but significant talk.

Dr Bartolo starts to talk while images of Lampedusa appear on the screen behind him. The first picture is The Lampedusa Cross (Croce di Lampedusa), made by an island’s carpenter from pieces of a boat which sank on 11th October 2013 off the coast of Lampedusa. On that day 311 Eritrean and Somali refugees lost their lives in the Mediterranean and 155 others were saved by the island’s inhabitants. That cross bears witness to the extreme humanity of the people of that small slab.

Sometimes they ask me why the people of Lampedusa haven’t gotten tired of all this and just welcome everyone. Yes. Lampedusa has been welcoming migrants for 25 years. Never a wall or barbed wire. No one has been rejected. Why do we do that? Because islanders welcome everything the sea gives them. We welcome everyone because, you see, they are human beings. They are like us.

On his island, which is located on Europe’s busiest sea migration route, there are no barriers, no walls, no borders.

And even Dr Bartolo doesn’t hide behind barriers. He doesn’t filter his words while talking about what’s happening in Lampedusa.

It has to be like this. No censored pictures. No hidden feelings or emotions. This is the only way to raise awareness and really start a dialogue.

“One night a boat came with about 250 people. I had to do the usual medical examinations and make sure there were no infectious diseases. In the hold it was pitch-dark and then I realized I was walking on the dead bodies of 25 boys.“, Dr Bartolo points at the grotesque picture behind him, bodies that seem to melt with one another.

They died of asphyxiation in about 15 minutes, after being hit with pipes by unscrupulous smugglers. They just wanted to get some air. What shocked me the most was that they had no nails and blood was dripping down the walls of that boat. They tried to get out. They didn’t make it.

Pictures and stories keep flowing. Boatloads of people. Corpses. A mother with her new baby girl, born in a dinghy in the Mediterranean, the umbilical chord tied with a clump of hair. “When I see this picture I start to feel bad. The mother gave birth on a dinghy and pulled her hair out to tie the chord. There was nothing else she could use.”

“This is what happened on 3rd October 2013, the day that changed the lives of all of us and especially the people of Lampedusa. That day they were 368.” The screen shows us the pictures of hundreds and hundreds of body bags.

That night they called me saying a ship had just sunk. I was at the dock and the first boats to come were those of the fishermen of Lampedusa. They were the first to intervene. A small boat took 49 people. They were not fine, but they were alive.

Then a fishing boat came with 19 survivors and 4 dead bodies on the poop deck. I checked a girl who was among the dead, in a plastic bag. As I always do, I took her wrist in my hands and I heard a heartbeat. And then another one. She was alive. We ran to the hospital where we intubated her and performed CPR and finally, after 15 minutes, her heart started to beat again. Her lungs were filled with water and she was in a coma, so we transferred her to Palermo by helicopter.

She was discharged after one month and she lives in Sweden now. After three years, on 3rd of October this year, she came back to Lampedusa and I can’t explain the joy I felt. Seeing this beautiful girl, whom I had only seen dead, coming towards me.

And she told me ‘I am Kebrat’. She was four months pregnant. She asked me if I wanted to be her son’s godfather; we’ll see!

Dr Bartolo smiles and we start clapping. Then, he becomes serious again. The small glimmers of success and life seem to fade away in front of what happened next.

“After Kebrat only dead bodies. 368 body bags to unzip. Do you see that white coffin?”, he points at the screen. “Inside that coffin there are a mother and her child. They were found with the umbilical chord still attached. I didn’t cut it and I put them together in the same coffin.” He’s fighting back the tears.

People tell me: you’re used to it. But it’s not true. How can you get used to it?

Over the many years that Dr Bartolo has been welcoming migrants and refugees, the way people attempt the crossing has changed as well as the kind of injuries and diseases from which they are suffering.

“Their diseases are due to the extremely difficult journey. Hypothermia, dehydration, scabies. The feared scabies, which is in reality nothing serious. They don’t bring any kind of infectious diseases. And then there’s the newest one, what I call ‘the dinghy disease’.” Dr Bartolo explains that a lot has changed in the last years.

Migrants used to arrive on Lampedusa independently on bigger and sturdier vessels powered by diesel. This happened until 2013 when, after Italy’s deadliest shipwreck, just a few hundred meters off Lampedusa’s coast, the country responded setting up Mare Nostrum.

Dinghies carrying migrants in international waters are intercepted and Mare Nostrum operates within 130 miles off Lampedusa’s coast. Other countries are now working together with Italy.

Even the ones that do not want migrants and refugees. They just save them and leave them in Italy. From that moment, when Mare Nostrum was introduced, smugglers started to use smaller dinghies and less-seaworthy vessels, powered by petrol. Petrol often spills inside the boats and mixes with water. This mixture is extremely dangerous and clings to people’s clothes and skin leading to chemical burns and skin peeling off.

Pictures of burnt bodies appear on the screen. “These injuries are extremely serious but I’ve rarely seen people complaining and this shocks me. They’ve been through hell and they don’t complain.”

Chemical burns are very difficult to treat and often lead to death. “That’s what happened to Favour’s mother. A lot has been said about this little girl, but the fact is that we have seen and we keep seeing too many children exactly like her.”

And if we talk about violence and trauma, it’s the women and girls who suffer the most.

They all arrive raped, some of them pregnant. Even the little girls of 12 or 13. They ask for abortions even if they are not allowed in their culture. They can’t even look at the screen when I show them the baby they’re carrying. Some of them simply want to die.

Dr Bartolo shows us the video of a boatload on the dock of Lampedusa. Hundreds of people, injured women, the run to the small hospital.

The next video is something I will never forget. It shows the recovery of the bodies of those who lost their lives in the Mediterranean on 3rd October 2013.

There’s the body of a child. “This was the first child I saw when I unzipped the first body bag. There were too many kids.” He’s fighting back his tears again.

This is man’s atrocity. We’ve created this! Now we have to do what we can because it’s simply right to do so. They are people. Flesh and blood. Not numbers. They’re often seen as mere numbers. There were 200, 500, 900. I’ve seen thousands of them dead. No-one can get used to seeing the dead. For me, even if we save only one, it’s worth it. The priority has to be to save lives, open the borders, give them the life they’re fighting for.

I leave the hall feeling heavier. Pictures and videos stick in my head. The words of Dr Bartolo resound in my ears. Especially those he said to me at the end of the conference, when we had time for a brief talk.

When you are a doctor, remember to stay human. It’s the most important thing. If you see humans and not patients in front of you, you’re halfway there. Never forget to stay human.

Stay human.

Open the borders.

Open your heart.

Just let them in.