Legal – but necessary?

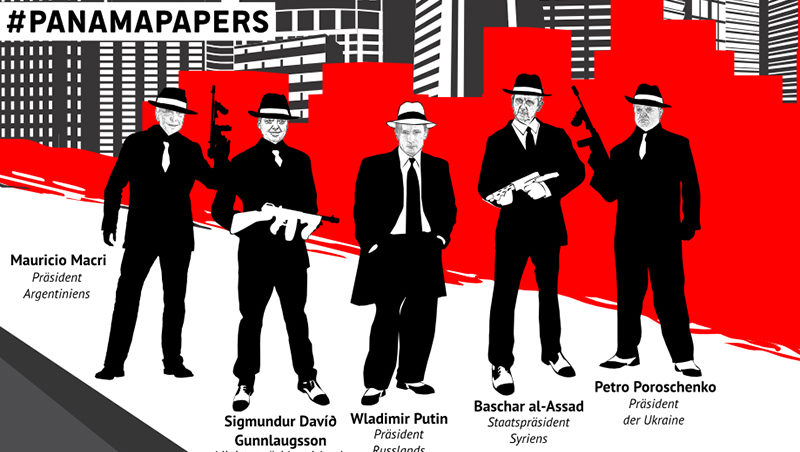

The Panama Papers: 11.5 million documents that shed light on a parallel society almost forgotten about, in times of the refugee crisis. Looking at 214000 shell companies and thousands of names, including many celebrities from sports, business and politics, one is extremely hardpressed to believe in individual cases. Also because Mossack Fonseca is only the fourth largest law firm in the world to offer these – oftentimes socially harmful – services. And as the self-tests of Phoenix and the left wing MP Fabio de Masi show, the business model apparently continues to flourish.

Now, it is not illegal as such, to set up shell companies – if you wish to hide your money from the jealous wife or if companis (legally) want to save taxes via the royalties trick. Nevertheless, according to tax experts, the vast majority of these constructs is established to commit crimes (tax evasion), whitewash criminal money or – as in the case of Syria and North Korea – to circumvent international sanctions (e.g. in order to buy weapons).

Given the overwhelming number of criminal applications, one wonders why such constructs are legal at all, especially since this “offer” is addressed only to a very small portion of the world population. Why is it necessary to conceal the ownership of a company, partially (see Phoenix Doku above) via five or more nested companies? ‘Handelsblatt’ went after the question of what legal reasons there can be to open up shell companies in tax havens.

The argument that the rich must protect themselves against extortionists and other criminals (see case Reemtsma) by means of trusts, is understandable, but does not really hold water. Even if a criminal may not be able to determine the exact capacity of a person – on the basis of cars used, land and aircraft owned, or through newspaper reports or Society presence, it is pretty easy to conclude that a lot of money must be present with his target.

The task of organizing a worldwide inheritance (see case Gunter Sachs) may be predestined for a trust, much like that of purchasing a valuable work of art. But can the number of cases where artworks were legally purchased or legal inheritances are passed, justify the majority of illegal activities and attempts to conceal evidence from government authorities? And if one must apparently assume that banks and auction houses are deeply infiltrated by criminal organizations, which want to acquire said art, it seems high time, the put the issue of corruption and criminal justice at the very top of the agenda of the countries concerned.

Excluding liability may sound quite funny in the case of a slippery banana skin. But when it comes to product liability or similar state regulations, it would be highly problematic to circumvent these, using company constructs whose owners are not known.

Remains the concealment of trade secrets or interests (startup investments): if Apple wants to participate in a promising company without alerting the competition, a shell company that obscures the ownership structure, is the appropriate means. With this apparent reason, the question arises whether this necessarily requires a company in a tax haven, or if (as a legislator) one could not provide suitable legal constructions in the country of origin, which take into regard both the interests of the company as well as the local tax authority.

Since the fear of criminal energy seems to be quite high with the wealthy and with companies and they therefore take refuge in the anonymity of tax havens, imagine for a moment, a criminal organization stealing data from the British Virgin Islands. It is not to be expected that the measures and possibilities of data protection or the protection against criminal assault on a small island in the middle of nowhere are much higher, than in western industrialized countries. For even if a company identifies no owner to the Austrian Treasury, this data is still stored somewhere – most likely in financial institutions’ computers in tax havens. Whether or not one can buy more long-term security for one’s savings that way, remains to be seen. At any rate, the certainty that the domestic Treasury receives no insight into the activities of the company, is given. And for the vast majority of mailbox constructs, this is probably the dominant motivation.

Despite far-reaching agreements such as that of the OECD, which becomes effective in 2017 and in which 60 states (including hardly any tax havens) participate and automatically exchange control data between their tax administrations, tax evasion can only be curbed by either putting pressure on the the tax havens to join such agreements (Panama refuses in the specific case), or by tackling the letterbox companies as is being tried in Germany with the transparency register (but unfortunately only half-heartedly).

Translation from German: Serena Nebo

Credits

| Image | Title | Author | License |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Panama Papers | PANAMA + FREEPIK | CC BY SA 4.0 |