Experts report: How Dangerous is Microplastic? – Part 1

Event data

- Datum

- 24. 1. 2017

- Host

- Forschungsverbund Umwelt der Universität Wien in Kooperation mit dem NHM Wien

- Location

- Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Obere Kuppelhalle

- Event-type

- Podiumsdiskussion

- Participants

- Prof. Thilo Hofmann, Leiter des Forschungsverbundes Umwelt, Uni Wien, Geologe und Professor für Umweltgeologie, Uni Wien

- Gunnar Gerdts, Mikrobiologe und Wissenschaftler am Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtzzentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung auf Helgoland

- Gerhard J. Herndl, Meeresbiologe, Dekan der Fakultät für Lebenswissenschaften an der Uni Wien, Leiter des Forschungsverbundes Umwelt, Uni Wien

- Dr. Wilhelm Vogel, Zoologe und Biochemiker, Abteilungsleiter für Oberflächengewässer im Umweltbundesamt

- Prof. Ulrike Felt, Professorin für Wissenschafts- und Technikforschung, Dekan an der Fakultät für Sozialwissenschaft an der Uni Wien

- Christian Köberl, Generaldirektor des Naturhistorischen Museums Wien

- Regina Hitzenberger, Vize-Rektorin Uni Wien

- Birgit Dalheimer, Ö1, Moderation

The “Forschungsverbund Umwelt” (Environmental Research Group) deals with the consequences of human intervention in the ecosystem. At the first event of a series entitled: “Environment in Conversation”, the question discussed on 24.1.17 was: “How dangerous is microplastic?“. Gunnar Gerdts, microbiologist and scientist at Helgoland, Prof. Thilo Hofmann, geologist, Professor of Environmental Geology and Head of the Environmental Research Group at the University of Vienna, Gerhard J. Herndl, marine biologist, Dean of the Faculty of Life Sciences, Dr. Wilhelm Vogel, zoologist, biochemist and Department Manager for Surface Waters at the Federal Environmental Agency, as well as Prof. Ulrike Felt, Professor of Science and Technology Research and Dean at the Faculty of Social Science at the University of Vienna took part in the discussion.

Greeting:

Christian Köberl:

According to current estimates, by the year 2050 the mass of plastic in the oceans will match that of fish. This is a danger to the environment and a significant human interference with the environment. We begin with the question of whether, by introducing new substances into the environment, we have initiated the new earth age of the Anthropocene.

Regina Hitzenberger:

Environmental sciences are very important, which is why the association of environmental sciences was established. Consequentially, this event is taking place within the framework of the Environmental Research Group.

By establishing this network by means of a merger of different faculties, the visibility of environmental research is to be significantly increased. There is much research at different faculties, the association allows cooperation here.

Prof. Thilo Hofmann:

The environmental research team, founded at the University of Vienna, brings together researchers – there are very complex issues, especially in the environmental sector, such as climate change, oceanic acidification, microplastic and environmental pollution, and most of these are topics that cannot be addressed within a single discipline – this is not an issue for one specialized field to look into, here we must work together.

The University is doing its part by addressing the subject and by conducting research projects, but this is not enough. We also have to go outside – especially in environmental research – and communicate what we are doing and what we want to discuss. We are looking for dialogue today.

Microplastic – why do we start with this topic? It is a topic that has been very strong in recent years. However, it has been on the table for 40 years. However, in the last 10 years, it has been discussed more intensively, and one would think that we know a lot about it. After all we hear about new harmful substances and catastrophes every day, and so we want to classify this today. Is it significant, is it insignificant? How important is it? In other words: How dangerous is microplastic?

Moderation: Birgit Dalheimer, Ö1

The sea is not only where the largest amount of plastic waste floats, but in addition there is also a large quantity of microplastic. These are – as one of the definitions – plastic particles smaller than five millimeters. This microplastic occurs in all seas up to the Arctic ice. This is a verified fact! What is not known for sure is the extent to which these microparticles damage marine organisms, or whether they can ultimately be dangerous for humans.

Dr. Gunnar Gerdts, you regularly take water samples and examine them in your laboratories. May I ask you directly for an assessment to answer tonight’s question: How dangerous is microplastic? Is microplastic just a hype, a cosmetic problem, or why are we actually discussing it today?

Gunnar Gerdts:

I began to look into microplastic about five years ago, because we were wondering if any garbage adrift in the sea might transer pathogens . And then I asked myself the question: What is the basis of this biofilm? Had I not asked myself this question, I would not be sitting here today having to answer the difficult question of whether or not this is dangerous.

What we know for sure is that macroplastic is a major danger to the ecosystem. We all know the images of starving birds, of whales eating ghostnets drifting in the sea. We know that this has an impact on the ecosystem.

However, we know relatively little about smaller plastic parts. This is due, on the one hand, to the fact that the effort required to detect microplastics in the sea is quite high. On the other hand, many mistakes were made in the beginning, which may have caused this hype: many false figures were published. In the meantime, we can assess this a little better, the experiments are carried out more elaborately and we know more about microplastic in seas and rivers.

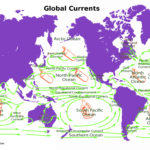

What’s still missing, in my view, is a systemic combination that not only examines the systems individually, but also takes into account the fact that the ecosystems belong together: the rivers are connected to the coasts and the seas, and the sea currents distribute anything over the whole world up to the mentioned polar regions where the microplastic concentration is enormously high.

Is that dangerous? I find it unaesthetic, and in principle, man should consider whether it is right for this stuff to be in there, because after all we are the polluters, we put it into the ecosystem. But whether this is ultimately harmful, cannot yet be said conclusively.

The statement, we do not yet know all that much, certainly not enough – that seems to be dragging through the subject matter. Thilo Hofmann, you have a good 20 years of experience in the research of nanoparticles and also see some parallels to microplastics. What do we know about how this microplastic comes into the sea – from the fibres we wash from our clothes, from the cosmetics we use, or from the disintegrating plastic bottles?

Prof. Thilo Hofmann:

If we start from the microplastics in cosmetics (for exfoliation, etc.), the question arises: Does this play a role at all, is the quantity of it important? What we know very well is the global output of plastics, because we know the data on how much is produced. Now, one would think that a city like Vienna should know exactly how much plastic is in circulation, and that is indeed the case. However, we do not know at all how much of this is actually introduced into the Danube, nor by what means.

What is not covered by the sewage treatment plants? The macroplastics can be captured well, but the smaller the parts are, the more difficult it is to estimate its amount. If you look at what enters the oceans, 10 million tonnes, and then look at the estimates and the uncertainties – they are huge! It was surpring to me as well, just how great the uncertainties still are when it comes to microplastics.

We therefore neither know exactly how much enters the environment nor how it gets there. The microplastic in the sea, however, was the reason for the attention this topic is getting. Gerhard Herndl, you are on the Advisory Board of the Ocean Clean-up Initiative, which was initiated via Crowdfunding by a young Dutchman and has set itself the goal of taking the plastic out of the oceans. You were out at sea a lot; what could you and your team actually observe? What about the occurrence of microplasticity, and what consequences have you already been able to prove?

Gerhard Herndl:

Above all, it can be observed that we produce an abundance of plastic: the production of plastics worldwide has doubled from 140 million tonnes in 2001 to 280 million tonnes in 2013. If we now take Mr. Köberl’s image, of there soon being more plastic than fish in the sea, it can be said that globally we are currently producing three times as much plastic as the amount of fish we take from the sea.

And this plastic which we produce reaches the sea sooner or later. These are predominantly parts made of polyethylene and polypropylene, which we find drifting on the surface. This is not uniformly distributed in the sea, but collects in the whirlpools caused by the sea currents. This is what we call the “Greater Plastic Garbage Patches”.

But these are only the larger parts. If we talk about microplastics, we would also consider plastic particles smaller than three millimeters. These are difficult to collect though, because we would also gather up many plankton organisms. So, as a rule, these data are limited to larger particles from three millimeters upwards.

From these calculations, however, we now find that there is actually too little plastic on the surface, there should be more. This means that some plastic sinks through the water column and then finds itself in the sediment.

The problem is therefore very complex, because, on the one hand, we have the actual concentration of plastic particles to investigate: What is on the surface, what sinks into the depth? And then there’s the question: Are there any organisms that can break this down in any way? Micro-organisms also play a role, in the biofilm and ultimately also in degradation, as well as solar irradiation, because these large plastic bags are becoming increasingly fragmented and finally also turn into microplastics. Ultimately, it will also play a role in the food network, and that has not yet been sufficiently researched.

I would like to know what all this means for the authorities. Dr. Wilhelm Vogel, one might say that the Environment Agency is a kind of bridge between society and politics, and makes recommendations based on its own and commissioned research. In cooperation with the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences (Umweltbundesamt), the Umweltbundesamt investigated the plastic content in the Danube in 2015 in connection with microplastics. What do you consider as the next steps, what should policy do in this regard?

Dr. Wilhelm Vogel:

As far as the general view of the subject is concerned, I would say the following: five years ago, marine plastic was already anchored in people’s consciousness, the problem was known to environmentally conscious people. The fact that plastic in general and, above all, microplastic could also pose a problem, however, was not known.

In 2014, a study was conducted at the University of Vienna, in which it was found that more plastic particles than fish larvae were present in the shallow water area of the Danube. This led to the question being raised of what effects this might have when fish eat the plastic, and whether or not this is dangerous. There has been a huge media hype, the newspapers were full of it, and politics and industry – especially Borealis as a big producer – were attacked. Subsequently, the survey of the status quo was commissioned.

It was an elaborate study with the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna. For this purpose, large net bags were sunk in the Danube in order to sample the entire range of material carried, and to determine the location and quantity of microplastic present in the water. We saw that there was much plastic on the surface, but of course much of it sinks and finds itself again in the sediment, because it is as heavy or heavier than water from mineral additives. We have estimated that 41 tonnes per year are transported down the Danube, and about 10% are of industrial origin – ie from industrial production and transport.

Concerning the fear that this might affect the fish, I can say that we were not able to find any plastic in fish stomachs and guts. But this might look completely different, specific to species. I am not saying that this is not damaging, but only that there is nothing inside the fish. Whether it is harmful or not is very hard to determine at present. There is still a great need for research.

There is a clear commitment from the administrative side – for whom I am here today – that “plastic has no business in nature.” Plastic is an enormously valuable raw material, it has great properties for certain projects, but it has to be applied according to its characteristics. One of them is its enormous durability, the persistence, which is causing us huge difficulties in nature.

The Ministry of the Environment has made a ten-point plan to harmonise methods and measurement standards with scientists. When we talk about plastic in the Danube, you’ll ask: Well, is that much? And I can only say: No idea – I do not know whether it is harmful, or how much of it is present in other places. The establishment of EU limits has been called for – but exact definitions are needed beforehand.

The network of the European environmental agency, which consists of environmental agencies from 33 countries, goes a little way beyond the EU and represents tremendous knowledge because it brings together the experience of 33 countries. And, of course, we also hope that, in the European research programmes, the appropriate funds will be made available.

What does any of this have to do with us now directly though, what can it mean for our actions? Ulrike Felt, you have been intensively engaged in the interaction of science, technology, society and politics for over 20 years. An ever-recurring subject of your research is the question of responsibility – who carries what responsibility for technical and scientific developments which could possibly pose risks or dangers, and at what point? Who is responsible in a state of total insecurity about the actual consequences of microplastic that we all bring into the environment on a daily basis through our lives in one way or another?

Prof. Ulrike Felt:

The question of microplastic is an extremely exciting one because it demonstrates very nicely how we deal with technical innovations and how difficult it is to recognise how far we can go. Plastic waste has been discussed for decades, and microplastic has now raised it to a new level because it is a matter of how we sensitise society to a problem and how this can be achieved at all.

And the question of the visibility and invisibility of problematic situations is indeed one of the great difficulties. The question is: How do we establish something that we basically cannot perceive? The numbers that have been named have already touched on the problem:

Plastic is the success story of the 20th century in the sense that it has sucessfully been brought into almost every area of life. You just have to look around: even if you are very conscious about your lifestyle, enormous amounts of things in the world in which you move will be made of plastic. Where do we even begin adjusting and considering which elements in society we can replace, and with what?

We can establish that certain companies bring this into the environment, but, on the other hand, it is, of course, a distributed problem. If we now say that this is an institutional responsibility and is calling for the legislature to finally give us guidelines, then we do not have to do anything ourselves as long as guidelines do not exist.

Or we, in Europe, could decide that, in the sense of a precautionary principle, we will now at least begin to think about what is to be done in which areas – even if we cannot yet determine what impact it has. Because we assume that plastic simply doesn’t belong where it currently ends up. How difficult it is to document this scientifically has already been expressed. The question is: are we as a society going to wait until we can assess it scientifically? Until then, the problem might have already expanded to a magnitutude that we can no longer cope with.

We really have to think about how we are introducing products into our society and where there are even any possibilities for intervention.

So, returning to the issue of responsibility, we are likely to have to do both: we must think of creating distributed forms of responsibility. We have to set up awareness-building measures wherever we consider plastic to be dispensible but, on the other hand, we have to look at what we can achieve institutionally at all, whether regulation is even sufficient.

But there is something quite different attached to this. Microplastics is a good example of unjust distribution; who bears the burden of microloading and who reaps the benefits of the production and distribution of certain goods.

This summary contains the statements of all present researchers on microplastic problems in general. In the second part, the experts will look more closely at questions from the audience.

Translation from German: Serena Nebo

[…] The experts in the dicussion round, “Environment in Conversation”, Gunnar Gerdts, Prof. Thilo Hofmann, Gerhard Herndl, Dr. Wilhelm Vogel and Prof. Ulrike Felt asked for audience questions. Since these were both asked and answered very extensively, they follow below, separately from the impulse round. […]